By Tao Tan, November 5, 2025

In its first nine months, the Trump administration has thoroughly disrupted the American higher education landscape. It has cancelled federal grant funding, pressured university leaders to resign, and circulated a draft compact that ties preferential access to future funding to institutional policy changes. Critics call the administration’s actions overreach or even extortion. Supporters see this as long-overdue accountability.

The controversy has at least exposed a deeper structural truth. The storm now hitting American higher education did not start on January 20, 2025. Its conditions were created almost eight decades ago, when universities began building their budgets around federal aid, federal research, and federal policy. Successive programs, such as the GI Bill, the National Science Foundation, and Title IV aid, all deepened the partnership between the federal government and higher education.

The Trump administration has simply highlighted the reality that even private universities in America are highly dependent on public support. Today, on average 25% of all university revenue either originates in or is facilitated by the federal government.

Many faculty earnestly believe in the inviolably private character of their institutions. Even administrators, often more aware of their institutions’ federal entanglements, may not realize how systemic and universal this interdependence has become: In 2025, nearly all universities depend on public money—which depends on public trust and public confidence.

The most constructive response to the recent disruption of that relationship is not defensiveness but reflection: how should universities govern themselves so as to reflect the reality of their publicly-funded character, and earn back the trust and confidence of the taxpayers who support them?

From the Bodleian to Berlin to Vannevar Bush

The contemporary American university has no real parallel in history. It is the fusion of three great academic traditions: the English, the German, and the postwar American.

The first American institutions were not universities at all, but rather colleges modeled on Oxford and Cambridge’s constituent colleges: small residential communities devoted to educating clergy and civic leaders. Later, in the 19th century, German philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt promoted the revolutionary idea that a university should not only transmit knowledge but create it. His model at what is now the Humboldt University of Berlin joined research and teaching, and sheltered them under the then-novel concept of academic freedom. American academics who studied in Germany brought the model back to institutions such as Harvard, Brown and the University of Michigan, producing a synthesis of the English and German traditions that created unique incentives for excellence and quickly propelled American universities past their European peers.

Federal support accelerated the ascension of the American university. The Morrill Act of 1862 opened the first pipeline of public investment into higher learning. But the real turning point came during World War II, when former MIT Dean Vannevar Bush led the Office of Scientific Research and Development. His agency channeled the equivalent of billions of today’s dollars into universities to produce radar, jet engines, mass-produced penicillin, early computers, and, in the basement of Columbia University’s Pupin Hall on the Upper West Side, something called the Manhattan Project.

After the war, both political parties chose to cement the partnership. Harry Truman created the National Science Foundation in 1950. Dwight Eisenhower, spurred by Sputnik, built on it with DARPA, NASA, and the National Defense Education Act.

From the fusion of English teaching, German research, and postwar scale emerged the modern American research university: publicly supported, independently governed, and unmatched in history. Most kept a liberal arts core, largely ignored in Europe and Asia, to sustain an educated and civically-minded citizenry.

Meanwhile, federal funding created a “virtuous cycle” of discovery where public dollars created new technologies, which seeded new industries, which generated new tax revenues that sustained further research. The result was a portfolio of intergenerational national assets, the backbone of American innovation and a cornerstone of our nation’s economic strength.

Snap Back to Reality

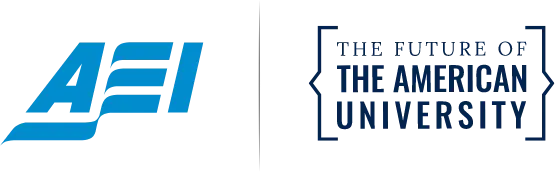

Eight decades later, the wartime arithmetic of Vannevar Bush has become structural to the whole university system. An analysis of university financial statements from the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) database shows that, on average, at least a quarter of all university revenue now originates in or is facilitated by Washington.

Federal dollars flow not only through research grants but through federal student aid under the Higher Education Act of 1965. International enrollment, which as a proportion of tuition revenue has grown by over 70% over the past two decades, depends on U.S. government-issued visas. Many universities also operate or affiliate with hospital systems that derive 40% or more of their patient care revenues from Medicare and Medicaid.

What’s striking is the consistency of that dependence. Large or small, public or private, doctoral research university or liberal arts college, elite or regional—all types of institutions of higher education depend on federal support for an average of 25% of their revenue. (These calculations do not include Medicare or Medicaid spending for affiliated hospitals, which likely approaches the order of $100 billion, so the true figure for universities with hospitals would be higher.)

This leads to a grim reality. Remove those federal streams, and few institutions could sustain themselves beyond a few months. Even the small number of institutions with large endowments would struggle to meet basic obligations like payroll and debt service as most of their assets are illiquid and legally restricted.

Some might object: what about the disciplines that don’t depend on multi-million-dollar labs or armies of research assistants such the humanities, the arts, the social sciences? Couldn’t universities simply return to their 19th century roots as teaching colleges, shut down or spin off “big science”, and shed federal support altogether? What about Hillsdale College, that perennial symbol of independence, which as a matter of principle, takes no federal money? After all, even Harvard thrived for three centuries before the postwar rise of federal research funding.

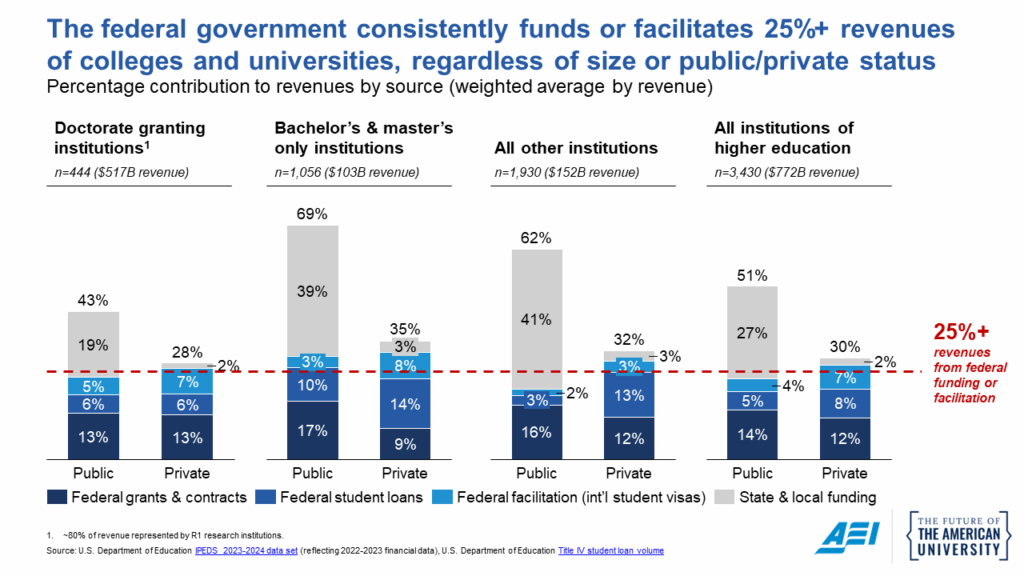

Not quite. Hillsdale is a small liberal arts college with no research enterprise, not a replicable counterexample for the national system of higher education. For most schools, financing through tuition is no refuge; 60% or more of private school tuition is funded or facilitated by government sources such as federal loans, grants, or the visa policies that bring in full-pay international students. In other words, public support comprises most of even what appears to be private revenue.

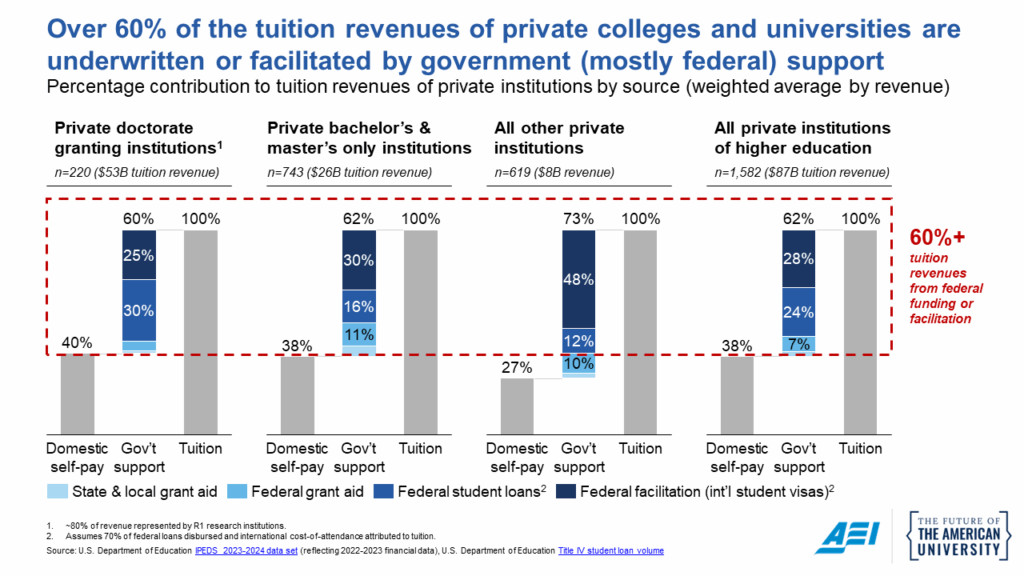

This is not a recent development. For decades, federal government support has quietly underwritten the entire system, regardless of whether universities are public or private. The chart below traces that steady reliance since 2004, which for both public and private institutions consistently hovers around the 25% mark.

The conclusion is both unavoidable and uncomfortable. Aside from a small handful of exceptions, universities in America are existentially dependent on public support. When the federal government began freezing funding, it forced universities to face that fiscal reality.

Reclaiming a National Asset

Federal investment in higher education has never been charity. It is better understood as a covenant, or dare we say, a compact. The American people fund access and discovery, and in return, colleges and universities support a civic mission, deliver scientific innovation, assist with social and economic mobility, and provide the civilizational means to secure America’s place in the world.

That bargain worked for decades, until both sides seemed to forget it. Some faculty and administrators began to see public funding as an entitlement, and some policymakers began to see the capacity to exercise regulatory oversight as an opportunity to exercise control. The result is mutual alienation. Some in the Trump administration seem to see universities as mendicant ingrates, and some universities act as if accountability were persecution.

Yet universities are intergenerational national assets. They helped secure victory in war, security in peace, and prosperity across generations. Far from being inaccessible ivory towers, the American people are deeply invested in these national assets. The return on that investment is bipartisan, intergenerational, and unmatched. The only real answer to a fraying of a relationship is renewal.

So how do universities reclaim their role?

First, universities should acknowledge the large stake that the American people have in them. The American people invest more than $300 billion each year in research grants, state appropriations, financial aid, and the like, and they have every right to expect a return. Higher education is the only sector that fiercely insists on autonomy while relying so deeply on public funding. Other federally supported sectors—think healthcare, utilities, or defense—acknowledge their relationship to federal policy because it is self-evident. Universities should do the same.

Second, they would benefit from being transparent about their value to the nation. The public deserves to see, in plain numbers and clear storytelling, the impact of its taxpayer investment: companies founded, jobs created, discoveries made, students advanced, patients treated, communities served. There should be no embarrassment in acknowledging that the American university should both seek truth and serve the nation that sustains it.

Third, they should welcome the full breadth of the country they serve. Public confidence has eroded in part because many Americans no longer feel they have a stake in the institutions their tax dollars sustain. The perception that universities are partisan enclaves, fair or not, cannot be ignored. The long-term remedy is not government-ordered ideological balance or token representation of conservatives, but a genuine effort to make universities feel like national institutions again, open to the convictions, doubts, and experiences of all Americans. Targeted investments in new academic units could help bring about this generational change in the faculty body while creating the conditions for new clusters of excellence to emerge by their own momentum.

Fourth, they should prepare for financial and demographic reality. The era of easy growth and ever-increasing amounts of no-strings-attached funding is ending. The population of high school graduates peaks this year. Institutions will need to rethink how they finance themselves and how they are governed. Longstanding assumptions on administrative staffing, revenue diversification, and cost models will come under scrutiny. New models should reward prudence as much as expansion. Failure to plan will see unanticipated downsizing, as we have seen at Washington University in St. Louis, Duke, Brown, Harvard, and the University of Chicago.

Fifth, reform must begin from within. The scale and complexity of renewal cannot be legislated or imposed by regulatory fiat; it must be owned by the universities themselves. Top-down reforms imposed by executive orders, even when necessary and welcome, can be undone with the stroke of a pen in 2029. And governments that learn to exercise leverage through financial means rarely relinquish it, regardless of whether they are conservative or progressive. The only path to sustaining taxpayer support and protecting institutional autonomy is earning bipartisan confidence in the academic mission before the court of public opinion.

Harvard’s Danielle Allen has suggested that universities should not interpret the proposed compact literally as a legal negotiation, but as an opening for a sector-wide conversation to identify reforms that could correct recent excesses and rebuild public trust, perhaps even leading to a legislative reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. This idea appears to have bipartisan resonance. On issues like pushing back against ever-encroaching compliance requirements and resulting administrative bloat, there is even potential for partnership with a government equally weary of waste. This is a test: if institutions claim self-governance as a prerogative, they must now prove they can use it well.

America does not need to nationalize its universities. It needs to recognize that they already serve a national purpose—and to govern them accordingly, as intergenerational assets held in trust for the American people, a system that has long helped make America great and can continue to do so. The romantic ideal of a wholly private university is more history than reality. For all practical purposes, America’s universities today are quasi-public institutions that must remember whom they serve.

Appendix: Data and Methods

All figures in this essay are drawn from the U.S. Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and Title IV federal loan volume statistics. A full analysis can be found here, with all assumptions documented and all data sources linked. SQL queries used to generate the results are included for any reader who wishes to replicate or extend the analysis.

My rough figure of $100 billion for the amount of Medicare and Medicaid funding hospitals receive is based on the estimate by the American Association of Medical Colleges that their member institutions provide 23% of Medicare inpatient days and 27% of Medicaid hospitalizations. The actual figure is difficult to estimate as there is wide variation in how universities consolidate the financials of their affiliated health systems, hospitals, and physician practice groups. However, a manual reconciliation of a sample of 20 R1 research universities with affiliated health systems show that Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements range from 5% to over 30% of revenues.

Data submitted to IPEDS reports patient care revenue inconsistently, sometimes broken out under hospital revenues (F2D13/F1B06) and sometimes consolidated into other line items. Moreover, the share of Medicare and Medicaid payments is disclosed in the footnotes to financial statements, but not as a separate IPEDS field. Future changes to IPEDS reporting structure might incorporate these more consistently to facilitate a more accurate and systematic study of federal funding to universities.